ARTificial Intelligence Exhibition

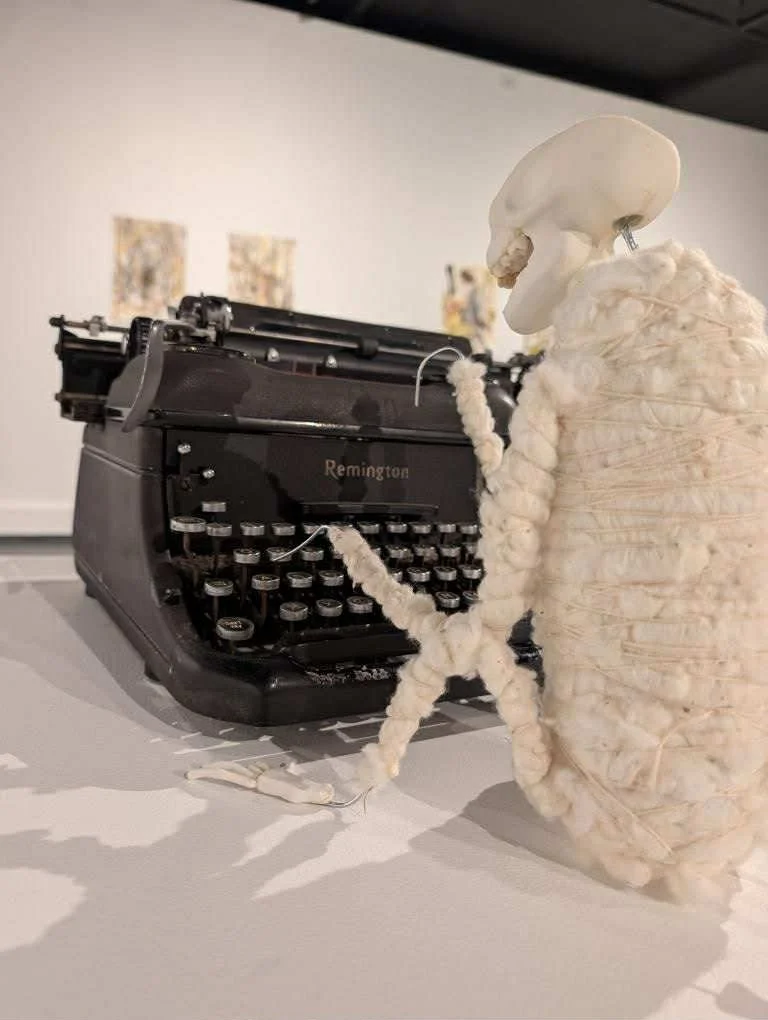

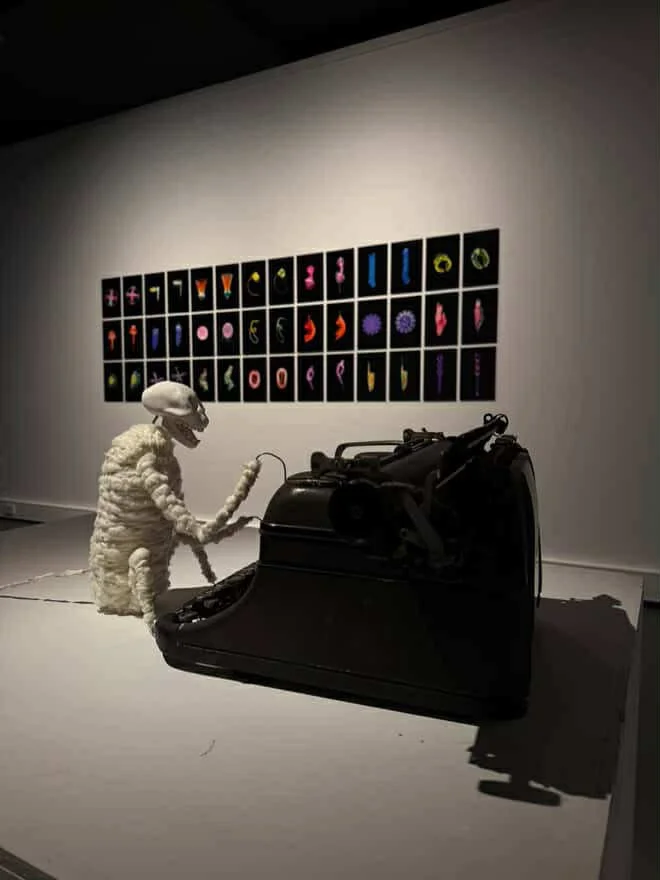

Christina Lowry, The Infinite Library of Babel 2025.

Porcelain, baby teeth, wire, foam, raw cotton, string, typewriter.

The infinite monkey theorem posits that a monkey hitting a typewriter keyboard for an infinite amount of time would eventually write Shakespeare. In this piece, the infinite monkey theorem is crossed with concepts from Jorge Luis Borges’ 1941 short story The Library of Babel, which conceives of the universe as an immense library of identical 410-page books, documenting all which has occurred, will occur and even some things which are erroneous. Using this theorem and story, this work examines how AI is used to construct knowledge, infinitely replicating information which may or may not be correct.

Pics 1 and 3 by Bree DiMattina.

ARTificial Intelligence

Fiona Cuthbert O’Meara, Rosie Lloyd-Giblett,

Christina Lowry, Joyce Lubotzky, Jude Muduioa.

Curated by Bree Di Mattina

Webb Gallery

Queensland College of Art and Design, Southbank

24 June – 5 July 2025

Curatorial Essay

Art is a mirror of society. Artists experiment and agitate. They reflect who we are and question what we stand for. Artificial Intelligence is the capability of computer technology to perform tasks typically associated with human intelligence. Enter prompts into an AI application and you can gather information or generate an image, video or animation. Previous generations of artists also faced technological advancements, such as printmaking, photography and video, with each of these innovations now accepted as art media. With AI becoming increasingly enmeshed with our lives, how does society reconcile the role of the artist and this technology? Is art a uniquely human endeavour, or can human creativity be combined with or even outsourced to AI?

The artists in this exhibition all draw their inspiration from the natural world. Humans, animals and the environment inform their practices. Can nature-based practices have a symbiotic relationship with AI, or are they the latest binary pair? Presented with this curatorial challenge, each of the five artists responded in a unique manner.

Rosie Lloyd-Giblett makes works en plein air. Working on paper with naturally derived mark-making materials such as charcoal and pigments, Lloyd-Giblett embraces chance elements, such as windswept paper, and natural textures, such as bark and soil rubbings. Not replicating or capturing a scene, she instead embraces the feeling and emotions stirred in her by the location. These works represent both the intangible feeling of the natural landscape and her emotional responses to it. The physicality of her making process and the embracing of chance natural elements give Lloyd-Giblett’s pieces a spontaneous, expressionist quality. While the works may look like a steadfast rejection of AI in art, they instead offer an affirmation of the role of the artist’s hand, emotions and physical presence.

Like Lloyd-Giblett, Jude Muduioa’s work Umbrial (2025) demonstrates the need to retain the hand of the artist in artmaking. Rather than working completely beyond the scope of AI, Muduioa instead chooses to build upon the capabilities of AI. Seeking information on Uranus’ moon Umbrial, she expands on the prescriptive results offered by AI, proposing a physical form for the unseen celestial body. Muduioa imagines a mysterious and sinuous, textured inky form for Umbrial, the central cavity of the sculpture alluding to the unknowability of this faraway object. By pairing the bland information offered by AI with her artist’s imagination, Muduioa, like Lloyd-Giblett, emphasises the physicality of artmaking.

Fiona Cuthbert O’Meara also builds on the work of the AI, using it to augment and inform her artwork. Foregrounding the physical human experience, in Transcending Bias (2025) Cuthbert O’Meara focusses on corporeality and healthcare. She posits that AI could be harnessed to support traditional medical processes, speeding up diagnoses and broadening healthcare and self-care options. By engaging with bodily sensations in conjunction with AI information, Cuthbert O’Meara’s installation proposes a multifaceted approach which transcends biases within current healthcare frameworks. Her work envisions a connected body, both physically and technologically.

The connections between nature and technology are also present in Hard/Soft (2025) by Joyce Lubotkzy. Lubotkzy methodically collects and catalogues plastic waste which washes up on her local beach. This synthetic debris lies upon the beach amongst the shells, seaweed and sea animal remains, like uncanny manmade corpses. Using AI, Lubotkzy then further blurs the distinction between the natural and unnatural waste, creating images of synthetic waste which resemble marine forms. Displayed together with the images of real collected waste, the generated images challenge the boundaries between organic and synthetic, real and imagined.

The boundaries between nature and technology, real and imagined are further interrogated by Christina Lowry in her work The Infinite Library of Babel (2025). Lowry’s work presents an unnerving metaphor for knowledge creation, mixing the infinite monkey theorem with the Jorge Luis Borges story of the Library of Babel. Knowledge, constructed ideas and the efficacy of information are mixed in the work which positions a non-remnant taxidermy model of a monkey as if operating a vintage typewriter. The outdated technology of the typewriter is juxtaposed against the contemporary non-remnant taxidermy model (made without any actual remains of a monkey). The only organic element in the taxidermy model is the bizarre inclusion of Lowry’s children’s baby teeth. Lowry questions the reliability of AI generated information, which is collected and collated from available information on the internet, much of which is unchecked, the AI randomly contributing to the recycling and creation of knowledge, often resulting in the recirculation of false or unreal information.

The responses offered by the artists in relation to the curatorial prompt are as varied as the proposed uses for AI. Uniting the works are themes of the body and truth. The importance of the hand of the artist and the ability of artists to make works which reflect a physical and emotional interaction with their environment continues to be the domain of the human, rather than technology. Likewise, a concern for the truth and the creation of knowledge, the human ability to discern between fact and fiction, emerge in the works. Art is often a barometer for broader society, and in the case of AI, the variety of applications and limitations of the technology can be seen in the artworks in this exhibition. Albert Einstein once said that “creativity is intelligence having fun”. As AI becomes more ingrained in society, humanity must decide to what extent should it be utilised and what joys should remain solely with humanity.

Bree Di Mattina

@bree_dimattina